Grey matters

A Firedog semi-tribute : Apple’s old master turned business into an art form

We recently published a 28 page Firedog Black and White paper – Entitled the “Art of equity”. The lead article looks at the relationship between creativity and business equity, via focussing on Apple’s Steve Jobs – Written a short while before he passed away. Have a look at the article below, which is included in full.

We recently published a 28 page Firedog Black and White paper – Entitled the “Art of equity”. The lead article looks at the relationship between creativity and business equity, via focussing on Apple’s Steve Jobs – Written a short while before he passed away. Have a look at the article below, which is included in full.

First, we would just like to add that we have been bowled over by the world’s admiration of Steve Jobs following his log off from planet earth. We’ve (Ok, just me) have always had a tricky relationship with this design icon. By all intents and purposes, as a designer, I should be right up their with my brethren holding a light to this amazing man.

But I’ve always wanted to be a little different, I guess – And have fought using Apple products as much as I could – Based purely on the logic of not being associated with others. That was until the iPhone, which for the first time, completely destroyed the competitive landscape. Not using this fine Apple product started to, quite unlike before, question your very intelligence behind your choice as a consumer.

The article which follows is a balanced view of what it takes to move beyond the soft and furry world of creativity to the dark and edgy world of global business – And how one man brought the two together with unbelievable success. Enjoy.

(Please note, as this was written before Steve’s passing so the tense may be incorrect and it may be deemed a little insensitive for some readers – Apologies Ed.)

Apple’s brand has perfection as its core value, and the tyrant-visionary who put it there has become as iconic as his products. Welcome

to the bewildering world of Steve Jobs.

He always wears the same clothes, stalks his own executives, and his terrified employees part like the Red Sea when they see him coming – yet his company churns out one zeitgeist-capturing product after another, and has become the world’s biggest and most important tech company. This is the world of Steven Paul Jobs, Apple co-founder and current CEO. Planet Jobs has an atmosphere somewhere between sulphuric acid and methane, and those who survive do so only if Jobs decides to dole out gas masks.

Back on Planet Earth – on April 1, 1976, to be precise – Steve Jobs co-founded Apple with his pal, electronics genius Steve Wozniak, with the modest aim of changing the world. That’s the thing about Apple: it is not a company, but a vision. Not long after its inception, this vision had spawned the world’s first microcomputer, the Apple II, followed by the Macintosh, the first all-in-one computer.

Back on Planet Earth – on April 1, 1976, to be precise – Steve Jobs co-founded Apple with his pal, electronics genius Steve Wozniak, with the modest aim of changing the world. That’s the thing about Apple: it is not a company, but a vision. Not long after its inception, this vision had spawned the world’s first microcomputer, the Apple II, followed by the Macintosh, the first all-in-one computer.

Jobs’ inspirations around this time included mysticism. In 1974, he travelled to India in search of spiritual enlightenment, and came back a card-carrying Buddhist, his shaven head atop billowing Indian clothing. He remains a practising Buddhist to this day, and has said that people who do not share his countercultural roots can never fully relate to his thinking.

He travelled to India in search of spiritual enlightenment, and came back a card-carrying Buddhist

Yet Jobs is a tangle of contradictions and hardly invites empathy. Take his spirituality. A Buddhist tenet is that the human condition is one of suffering, because it is in our nature to crave – yet no one in this world, or the next, craves perfection more than Jobs; he allows nothing, nor nobody, to stand between him and what he views as technological nirvana.

A sainted cultural and business icon he may be, but a serene Buddhist boss he certainly isn’t. Moody and with a white-hot temper, tales of Jobs’ personal abuses are legendary. He parks his Mercedes in handicapped spaces on the Apple campus, reduces subordinates to tears and summarily fires employees.

Author Robert Sutton was compelled to include Jobs in his bestselling 2007 book ‘The No Asshole Rule’, because “as soon as people heard I was writing a book on assholes, they’d start telling a Steve Jobs story”. Examples include a temper tantrum about the colour of the bolts inside a computer – because he wanted the technicians and geeks who opened it up to be impressed with its inner beauty. Another anecdote has him firing an Apple Store employee because he didn’t like the quality of the bags she’d ordered.

“I tried not answering the door,” reveals former Apple director Bill Campbell, “but he used to drive the dog so crazy I just had to.”

Further eyebrow-raising tales are recounted in Alan Deutschman’s ‘The Second Coming of Steve Jobs’. Two senior Apple executives told Deutschman how Jobs had stalked them, first with incessant calls to their work, mobile and home phones, and then – when they eventually gave up answering – with unsolicited evening visits to their homes. “I tried not answering the door,” reveals former Apple director Bill Campbell, “but he used to drive the dog so crazy I just had to.”

But Jobs’ unquenchable thirst for control goes even further than stalking Apple top brass, for he tries to manipulate the lives of his entire payroll. Jobs is a life-long, maniacally committed vegetarian – in fact, if vegetarianism had a paramilitary wing, he would be its balaclava-clad leader. At Jobs’ insistence, and to widespread dismay, the Apple canteen bill of fare almost overnight became a tofu-fest.

Then there is Jobs’ unchanging attire – a visible manifestation of control colliding with obsession. In his entire Apple career, Jobs has almost never been pictured wearing anything other than a black turtleneck sweater, faux-aged jeans and trainers. This reliance on uniformity, on consistency and predictability of appearance, is redolent of Brett Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho, whose mass-murdering banker anti-hero, Patrick Bateman, chooses his designer outfits with a similar pathological precision. It also suggests that Jobs sees himself as the uniformed leader – OK, let’s make that ‘dictator’ – of 34,300 foot soldiers.

Yet, as venture capitalist and former Apple executive Jean-Louis Gassée observes, “Democracies don’t make great products. You need a competent tyrant.” And if tyranny is a by-product of perfection as a brand value, then Apple’s shareholders don’t care a jot. Research firm Millward Brown Optimor (MBO) ranked Apple third in its 2010 Most Valuable Global Brands, behind Google and IBM, but ahead of Microsoft. MBO also estimated that year-on year, Apple’s brand value was up by 32% – the biggest increase of any of the 100 leading brands.

Yet, as venture capitalist and former Apple executive Jean-Louis Gassée observes, “Democracies don’t make great products. You need a competent tyrant.” And if tyranny is a by-product of perfection as a brand value, then Apple’s shareholders don’t care a jot. Research firm Millward Brown Optimor (MBO) ranked Apple third in its 2010 Most Valuable Global Brands, behind Google and IBM, but ahead of Microsoft. MBO also estimated that year-on year, Apple’s brand value was up by 32% – the biggest increase of any of the 100 leading brands.

Apple’s brand is defined by Jobs’ quest for perfection – of design and experience. Ah, ‘experience’. This bit’s intriguing, because where non-Apple consumers ‘use’ products, Apple customers ‘experience’ theirs. Part of this experience is defined by what Apple will and won’t let its customers do. It means iPhone users have to ‘jailbreak’ their devices to install third-party extensions and themes. iPad users are similarly restricted, because Jobs has locked out Adobe’s ubiquitous multimedia platform, Flash, from the iPad operating system, opting instead for a proprietary solution. Power and control are Jobs’ closest allies.

Where non-Apple consumers ‘use’ products, Apple customers ‘experience’ theirs

So what would happen were Apple ever to lose its dictator-cum-messiah? Would the brand suffer? Actually, the world already knows the answer to this, because Jobs and Apple have already parted company once before. In a 1985 boardroom coup, Jobs was forced out of his own firm by CEO John Sculley, whom Jobs himself had prised from Pepsi (with the words: “D’you wanna sell sugared water for the rest of your life, or d’you wanna change the world?”) Jobs’ big mistake was to forget Apple had shareholders. Sales of the first Macintosh computer in 1984 were catastrophically poor; while aesthetically wonderful, it was also underpowered, and no one had yet written any applications for it. Implored by Sculley to concentrate on the company’s profitable Apple II line, Jobs refused, and the board sided with Sculley. Jobs was out. “There was relief, as everyone had been terrorized by Jobs at some point,” recalls Larry Tesler, a computer scientist at Apple for 17 years. “But we were worried what would happen to the company without its visionary and founder, and without his charisma.”

He has this reality distortion field. In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything, but it wears off when he’s not around.

“Apple never recovered from losing Steve,” confirms Andy Hertzfeld, a key member of the Macintosh development team and one of Apple’s earliest employees. “It lost its soul. He has this reality distortion field. In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything, but it wears off when he’s not around.” Without Jobs’ wild-eyed quest for perfection, Apple drifted toward mediocrity, becoming a producer of beige boxes that, while popular with creatives, enthused few others. Over time, and under a succession of CEOs, the Apple brand became almost homoeopathically diluted. The low point came with the ‘Mac clones’ strategy of the mid-1990s, under which the company licensed its Mac OS operating system to third-party hardware vendors, who preceded to undercut Apple’s own products, driving the company towards extinction.

And what of Jobs during this decade away from Apple? He kept pretty quiet really, merely founding the Pixar animation studio in 1986, which he sold to Disney in 2006 for $7.4 billion, making him Disney’s largest shareholder and its most important board member. Pixar has become not only the most successful animation studio, but also one of Hollywood’s most successful movie studios. Its success has a similar narrative arc to that of Apple, being based in, and sustained by, Jobs’ drive toward perfection. Pixar films are leftfield, surreal even, yet they are cherished in a way that populist movies from other animation studios are not.

“That’s part of what Steve Jobs said early on,” says Dylan Brown, a supervising animator at Pixar. “He said he wanted to build Pixar into a brand, so that when people came to see a Pixar film there’s a certain level of integrity they can trust, even without seeing anything in advance about the film.”

In Jobs’ mind, the Apple brand has always been about design perfection – whether it’s software or hardware. As far back as 1982, he was actively encouraging his designers to think of themselves as artists.

During his enforced absence from Apple, Jobs also started another technology company, NeXT, which sold super high-end computers to scientific and academic markets. It was to be his ticket back into Apple, after the company bought NeXT for $429 million in 1996. At that time, ‘Apple’ and ‘beleaguered’ rarely failed to appear in the same sentence, but this was before Jobs began force-feeding perfection back into the Apple brand.

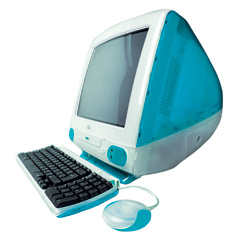

The company’s epic climb toward supremacy began when Jobs recognised that, during his time away, a design genius had joined the Apple ranks. London-born industrial designer Jonathan Ive was already working on a computer that Jobs realized could change the world all over again. His creation was 1998’s iconic transparent blue iMac. Within months, every electronic product – from irons to vibrators – were being designed using translucent blue plastic. Apple was back, because Jobs was back.

Everything, and yet nothing, had changed at Apple, because for Jobs, the Apple brand has always been about design and branding as art form – whether it’s software or hardware.

As far back as 1982, Jobs was actively encouraging his designers to think of themselves as artists. At this time, he took his Mac design team on a field trip to a Louis Comfort Tiffany exhibition, because Tiffany was an artist who was able to mass-produce his art – just as Jobs wanted to do.

He even insisted that his design team sign the interior of the Macintosh case, like artists signing their work. “He encouraged each one of us to feel personally responsible for the quality of the product,” Hertzfeld says.

The way Apple people work has not changed either. They turn in long hours with a passionate, almost messianic fervour, fuelled by the fear-tinged respect that Steve Jobs inspires.

Under Jobs’ guidance, Ive and his team have gone on to give us the iPod, iPhone and iPad. Perfection as a brand value requires ultimate control, which in turn requires the ultimate control freak.

Naturally, one day Jobs will again leave Apple, and it may be sooner than he’d wish. In 2004 he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Even cancer wasn’t safe from Jobs’ desire for control, and he tried to combat it with a special diet, before conceding nine months later that, yes, like everyone else he’d probably perish without surgery. Then, in 2009, he underwent a liver transplant, sparking rumours that the cancer had spread to his liver, which in turn created stock market panic, as the prospect of a Jobs-less Apple lurched into view.

When control freak extraordinaire Jobs does depart Apple for the final time, he might just draw comfort from the knowledge that only mismanagement on a cataclysmically dire scale can shake the Apple brand free of the quality with which he’s imbued it. Might.

I must admit – This article seems a little spooky revisited now. It will be very interesting to keep an eye on Apple’s fortunes, to see if they are indeed linked to Steve Jobs. The article is available to take away : You can download the full piece in a PDF here. (Thanks to Sean Ashcroft for original text)