Grey matters

Man <3 Machine

With the recent plans to close tube ticket offices, another means of communication with a fellow human being looks set to be cut off.

With the recent plans to close tube ticket offices, another means of communication with a fellow human being looks set to be cut off.

Soon, we will be able to buy our train ticket, grab a snack for the journey, and make our way to the chosen destination: all without having uttered one word or listened to a live human voice. Impressive? Or daunting?

With all this technology on tap, how are we feeling? Are our lives made easier? Or, is our frustration when a packet of chewing gum is too light to be recognised by the checkout machine just one example of when technology makes simple tasks unnecessarily difficult?

Checkout machines are potentially one of the worst culprits for giving technology a bad rep. Just type the words into a search engine and one of the top articles is Buzzfeed’s “20 reasons why self-service checkouts are just the worst.” These machines may look impressive, but they don’t seem to save much time.

Once you’ve trawled the database to find your item that’s bereft of a barcode, or hunted down a shop assistant because the machine has politely asked you to “please seek assistance” for no apparent reason, you wonder why you even bothered.

Communal relief upon discovering that most checkout machines have a mute button shows we prefer silence to the silky human voice that’s played on repeat all day, every day.inauthentic recordings sour perceptions

Yes, these inauthentic voice recordings definitely sour perceptions of technology. When stuck on a delayed train, who thought it would be a good idea to record a message informing frustrated passengers that “someone” is sorry for our delay?

This merely rubs salt in the wound; the person who recorded this is probably miles away, soaking up home comforts.

It’s the phoney nature of these messages that really gets our backs up. Sat Nav is another example of this – the pleasant-enough woman who calmly tells us to “turn around where possible” when it couldn’t be further from possible only riles us further. We feel foolish for ever having put so much trust in a machine, when it clearly has no concept of the situation we’re in.

Charlie Brooker has heavily explored the intrusion of technology in his Guardian column and television series, Black Mirror. Black Mirror certainly capitalises on this sense of “techno paranoia” The series certainly capitalises on this sense of “techno-paranoia”, depicting the dark side of our gadget obsession. Brooker writes that the series straddles the area between “delight and discomfort”.

From a nightmarish Orwellian future that runs on Apple software to imagining a Sky Plus system for your brain, Black Mirror considers technology in its extremes.

These are examples of technology both at its most frustrating and daunting, though: they undermine the infinite possibilities available. Does the future between man and machine really hold such bleakness?

Daft Punk’s Within is about an android gaining self-awareness

French electronic group Daft Punk convey the synergy between humans and technology in their music, taking a much less negative approach. Their self-directed film, Electroma, questions how we define “human” in a world bursting with technology.

This blurring of boundaries is similarly explored in their song Within, about an android gaining self-awareness: “There are so many things that I don’t understand, There’s a world within me that I cannot explain, Many rooms to explore, but the doors look the same.”Technology renders the difference between “human” and “robot” increasingly difficult to pinpoint.

Sorayama creates “gynoids” – sexy robots

Daft Punk’s fusion of human and robot has revived Hajime Sorayama’s artwork. Since the 1970s, Sorayama has merged technology and the female form with his images of “gynoids” – female robots – or “sexy robots”, as they’ve been dubbed. The gynoids are anatomically correct in form, but appear to have been made out of molten silver. Sorayama saw continuity between organic shapes and the ongoing evolution of engineering, stating: “Robots that are not organic in form have never made sense to me”. Is it now easier to envisage humans alongside technology, rather than distinctly different from it? “Robots that are not organic in form have never made sense to me”

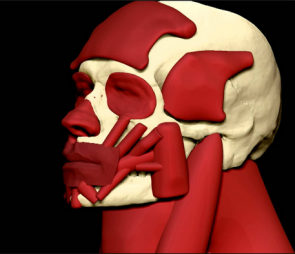

This brings us to the cyborg: a being with both organic and mechanical parts. Coined in 1960, cyborg creation began with the birth of HCI (human-computer interaction). Although cyborgs act out human functions, in some definitions, humans fitted with pacemakers might be considered cyborgs because technology is used to enhance biological capacities. It’s predicted that cyborg technology will form part of the human condition, distorting the lines between man and machine once more. So, what’s the difference? Morality, free will and empathy.

the cyborg: a being with both organic and mechanical parts

Cinematic depictions of humans and machines predominantly retain this key difference. Take Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Devoid of empathy, HAL 9000, the spaceship’s talking computer controls the mission and attempts to kill members on board. Fast forward 40 years, we have Duncan Jones’ 2009 film Moon. Sam is an astronaut on a three year mission with GERTY, his robotic companion. While GERTY’s selection of emoticons indicates happiness, confusion and sadness, its emotional scope remains limited.

It’s clear that thus far, we have predominantly experimented with technology in terms of intelligence and efficiency; we’ve barely touched on the emotional aspect. Our meek efforts include robots that are being developed for the elderly with the intention of providing comfort. Japan has created Paro, a baby harp seal that offers companionship rather than any tangible medical or physical support. One Japanese care home resident says that Paro “seems to understand human feelings” – it’s specifically programmed to behave in a way that the user prefers.

Paro offers companionship rather than medical or physical support.

This begs the question: if the evolution of intelligent technology produces robot pets that are extremely comforting while being devoid of the disadvantages of “real”, live pets, will the latter still appeal to us? For the elderly at least, robotic pets will certainly be much easier to maintain.

This argument takes us to the inspiration for Ridley Scott’s 1982 film, Blade Runner. Philip K Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? portrays a world that is so absorbed in technology, it lacks a sense of purpose. The protagonist, Deckard, owns an electric sheep. While he is attached to this sheep, he is convinced that owning a real animal will give his life the meaning it lacks. Despite all of this technology, social standing is defined through possessing a real, live animal.

The Voigt-Kampff test differentiates between humans and androids

As with Sorayama’s work, cyborgs and cinematic depictions, the novel probes the defining qualities that separate humans from androids. Again, we return to the notion of empathy. In Deckard’s world, advances in technology have made the difference between android and human virtually indistinguishable. Dick invents the “Voight-Kampff test”, which differentiates the two by measuring empathetic responses (or lack thereof), from questions designed to evoke an emotional response. Intertwining original and simulation, Dick’s novel forces the reader to reflect on where technology is taking us.

Do androids dream of electric sheep probes humans’ defining qualities

If Blade Runner is too fantastical for you, take the doctor/patient dynamic. Everyone’s probably experienced a doctor who lacks compassion, treating us as merely a diagnosis rather than a feeling human being. What’s more, doctors don’t always diagnose correctly. Imagine if we could perfectly code a machine-like therapist that continually employs empathy and tact as well as diagnosing every ailment correctly. Which would you choose: the perfect simulation of compassion and professionalism, or the imperfect human?

If we developed the emotional intelligence of robots, a one-sided relationship could be transformed into something that enriched our lives on a deeper level. As well as a sensitive companion, imagine a robot that reminds us about our diet when reaching for that slice of cake, or one that nags us to search for a job when we’re feeling lazy. Referring back to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Deckard falls in love with an android because she feels more approachable than his distant, human partner. Deckard falls in love with an android because she feels more approachable than his distant, human partner

We need to take a step back and consider our perceptions of technology, and of ourselves. Do robots perform structured, mechanical actions, or is this now us? Damon Albarn makes this point in his solo album, describing humans as “everyday robots on our phones.” Picture the throngs of people on your train, mindlessly sucked into the vacuum of dark, shiny screens, refreshing their social feeds purely through habit. Is this so dissimilar from our perceptions of robots? Ask yourself: who owns who – are we as in control of technology as we think?

Disney’s Wall-E similarly pursues this vein. In the story, humans are catered to by robots. Consequently, they are fat and sluggish in their routines, not bothering to engage their brains or bodies. Conversely, the robots in the film are closer to what we currently consider to be “human”; they care for one another and show distinct emotions. An ironic role reversal that’s not too hard to believe.the robots in Wall-E show distinct emotions

Just think: could robots save us from ourselves? Will they be programmed to anticipate these slack human tendencies, then jump in like some hyped up Nike training app? Far into the future, maybe humans and technology will harmoniously coexist, with chatty ticket booths, cash machines that apologise in advance for throwing so many dull coppers at you, and a lovely Sat Nav lady who asks about your travels. One day, maybe these daily interactions will drive us crazy in the right way.

Was this interesting? Here’s our quintessential list of films that explore the robots and humans dynamic:

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

Duncan Jones’ Moon

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner

James Cameron’s The Terminator

Alex Proyas’ Robocop