Design

Revolting moments in design

“Ye are many, they are few.” So ended the first May Day speech in 1890. Protests in Warsaw ghettos, uprisings against apartheid and the Portugese Revolution: May Day has a history of spirited revolt. Sparking both reverence and revulsion, design has repeatedly echoed this single-minded drive for change. We take you through the centuries.

“Ye are many, they are few.” So ended the first May Day speech in 1890. Protests in Warsaw ghettos, uprisings against apartheid and the Portugese Revolution: May Day has a history of spirited revolt. Sparking both reverence and revulsion, design has repeatedly echoed this single-minded drive for change. We take you through the centuries.

The 1800s saw a huge change in artistic direction. As well as experimenting with unconventional brush strokes, there was a dramatic shift in content. Much to the distaste of critics at the time, artists began painting subjects that had never before been broached.

Goya’s The Third of May 1808

Goya’s The Third of May 1808 has often been described as one of the first paintings of the modern era. Why? For perhaps the first time, method and subject are indivisible. Art historian Kenneth Clark describes it as the “first great picture which can be called Revolutionary in every sense of the word.” Goya presents the brutality of war in its rawest sense – traditional delicate brush strokes are nowhere to be seen. The unveiling of the painting intensified anger towards the French, fueling the uprising.

Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People

In France twenty years later, the artist Eugene Delacroix proudly stated: “I have painted a modern subject, a barricade.” His controversial war painting, Liberty Leading the People, commemorated the July Revolution of 1830. The painting broke with artistic convention as it depicts fighters from a variety of social classes. For this reason, the work was deemed to be republican and an anti-monarchist symbol – it was even hidden from public view during the king’s reign. It is now famous for representing romantic and revolutionary fervour -Coldplay drew on this when they used the painting as cover art for their 2009 Viva la Vida album.

Coldplay used the painting as cover art for their album, Viva la Vida

Art Nouveau

Moving on from nineteenth century paintings takes us to the fluid line of Art Nouveau. At the end of the 19th Century, this seemingly-innocent squiggle marked a conscious attempt to create a new, more liberal style. Alphonse Mucha became an overnight sensation with his romantic, swirling lines, expressing the decadence of the era without its vulgarity.

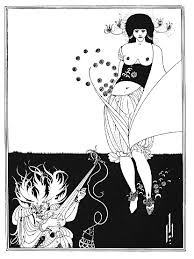

The same can’t be said for Aubrey Beardsley – his dark, perverse images set out to challenge Victorian artistic ideals of formality and convention. Satisfied that his lines went beyond far popular taste, the artist proudly stated: “If I am not grotesque, I am nothing.”

Beardsley set out to challenge Victorian ideals of formality and convention

Adding to the air of contention that his name evoked, Beardsley was the first art editor of The Yellow Book, the leading journal of the 1890s. With its lascivious content, the journal became synonymous with new movements of the period – Oscar Wilde was even carrying it when he was arrested in 1895.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, artists once more pushed the boundaries of what constitutes “art”. In this section, we look at influential movements in Europe, Mexico and Russia – and how they all moulded art into a form of political dissent.

Duchamp and the Dada movement

Rebelling against just about everything, instigators of the Dada movement created “anti-art” works. Duchamp daringly donned the Mona Lisa with a moustache and labelled a urinal as “art”. In 1917, many people ridiculed and rejected the urinal. Nowadays, Fountain is considered a major landmark in 20th century art – it marks a shift in the focus of art from physical craft to intellectual interpretation. Fountain is considered a major landmark in 20th century art

Russian Constructivism

Following the October Revolution in 1919, the Russian Constructivists used art and design as a political weapon. The movement’s graphic form couldn’t have been further from the swirls and flourishes of Art Nouveau. Using hard, geometric shapes in bold reds and blacks, these artists manipulated art into a form of propaganda. Clamouring for change and urging for a sense of social unity, the influential poet Mayakovsky declaimed: “The streets [are] our brushes, the squares our palettes.” The Constructivists used design as a political weapon

One of the most controversial and revolutionary of the Constructivist artists was El Lissitzky.

Famously stating: “I don’t belong to the birds that sing for the sake of singing”, Lissitzky was convicted that he could evoke change. The artist carried this belief to his deathbed, where he produced a poster rallying people to construct more tanks to fight against Nazi Germany.

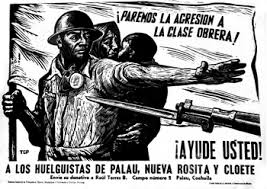

Leopoldo Mendez

Over in Mexico in the 1930s, Leopoldo Mendez produced propaganda against the rise of fascism. The artist is now considered one of the country’s most important artists from the twentieth century, as his work symbolises the ideals of the Mexican Revolution. Mendez did not seek fame or monetary gain; his goal was to work collaboratively and anonymously for the good of society. Mendez produced propaganda against the rise of fascism

Picasso’s Guernica

In June 1937, one of the most controversial and well-known paintings of all time was unveiled: Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. Critics argue that Goya’s The Third of May 1808 heavily influenced this painting with its bold, daring presentation of war. Guernica delivers both a hard-hitting political and artistic statement: it is a perpetual reminder of the tragedies of war.

The 1960s onwards saw yet more political upheaval. Artists cried out for change through experimenting with poster art and influential newspaper illustrations. We look at the Cuban Revolution, the Black Panther Party movement in America, and an iconic Margaret Thatcher puppet.

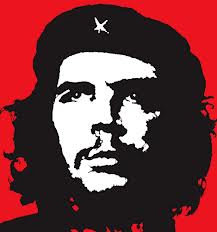

Jim Fitpatrick’s “Che”

In 1968, Jim Fitzpatrick revealed a poster that was to become one of the most iconic politically-motivated artistic statements from the twentieth century. Pinned to most teenage or student bedroom walls, his poster of Che Guevara captures the essence of revolution. Fitzpatrick’s “Che” poster captures unshakeable passion for a cause

The determination and resolution on Guevara’s face reaches out to a younger audience – it touches the youthful confidence that anything is possible when you are fixated on a cause.

Photographer Alberto Korda describes his image as portraying “absolute implacability” – it encapsulates Guevara’s unshakeable passion for a cause that became his life’s work.

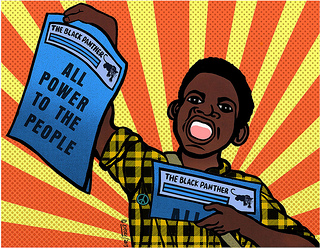

Emory Douglas

In America, The Blank Panther newspaper became an icon for the counterculture of the 1960s. Emory Douglas’ illustrations are now symbols of the Black Panther Party movement, a movement that protested for social change. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Emory portrayed the poor as “outraged, unapologetic and ready for a fight”. Popularising the word “Pig” in relation to the police, Douglas’ hard-hitting images and slogans inspired many to act.

Douglas’ hard-hitting images and slogans inspired many to act

Blek le Rat

In the 80s, Blek le Rat took art to the streets. Often called the “Father of stencil graffiti”, the artist painted stencils of rats – “the only free animal in the city” – on Parisian street walls. Like Mendez before him, the artist’s main motivation lies in social consciousness and the desire to bring art to the people, rather than being recognised in a museum. Blek le Rat is often cited as Banksy’s main influence.

Spitting Image

Illustrations, cartoons and graffiti have all constituted outlets for breeding disruption. Let’s not forget that television has played an equally significant part. Take the UK series Spitting Image. Satirising political parties in the 80s and 90s, the programme’s writers used the comic form to take a serious anti-Thatcher stance. Rubbing shoulders with a Nazi neighbour and dominating her terrified cabinet, Margaret Thatcher more than adequately filled the role of a power-crazed bully.

Spitting Image took a serious anti-Thatcher stance

Tracey Emin’s bed

In 1999, Tracey Emin shocked the world with a bed. Close to a hundred years after Duchamp’s urinal was dubbed “art”, Emin attempted the same feat by displaying an unmade bed in the Tate Modern. The evolution from a urinal to a bed that showcases intimacy in all its embarrassing glory reveals the progression of artists striving to expose moments that are ordinarily considered to be private.

As we move forward in the digital realm, artists are devising new ways to challenge the sociopolitical environment that surrounds them. Here, we look at the rise of street art, South Africa’s most controversial cartoonist, and the most powerful group of hackers around.

Stefan Sagmeister

Like Emin, Stefan Sagmeister is known for merging public and private spheres. Just take a look at his website, Sagmeister&Walsh, and its naked team photo. Sagmeister is known for merging public and private spheres

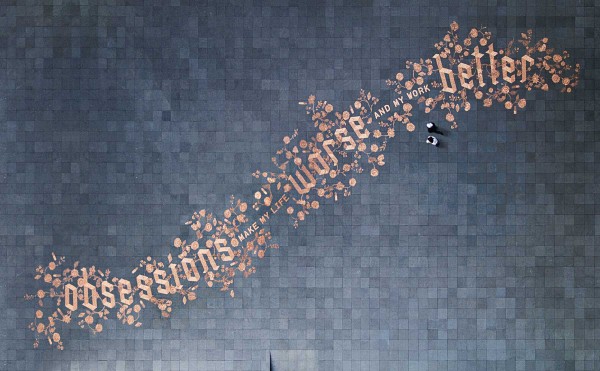

In 2008, Sagmeister filled Amsterdam’s Waagdragerhof Square with 250,000 cents that spelled out the message, “Obsessions make my life worse and my work better”. The artist intimately reveals that “while I fail to care about the right shade of green for the couch [or] the sexual details of an ex-lover, I do obsess over our work.” Leaving the coins for passersby to do with as they pleased, Sagmeister openly invited public participation.

Sagmeister filled Amsterdam’s Waagdragerhof Square with 250,000 cents

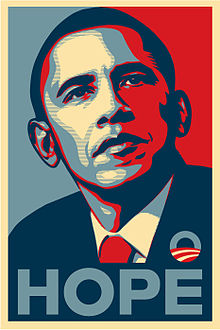

Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” poster

Also in 2008, Shepard Fairey created what is arguably the most politically symbolic poster for today’s young generation. This is his Barack Obama “Hope” print. When asked to produce something for the campaign, Fairey felt that Obama’s “power and sincerity as a speaker would create a positive association with his likeness.” The image rapidly became one of the most widely recognised icons of Obama’s campaign message, reflecting his slogan: “Change we can believe in.” Fairey’s poster became synonymous with Obama’s campaign message

Banksy’s “The Gleaners”

A year later, Banksy reinvented Millet’s nineteenth century painting, “The Gleaners”. Banksy’s preference for this painting reminds us just how far our definition of what is considered “controversial” has evolved.

A viewer from the 21st century may see a simple, pastoral landscape. Back in 1857, though, Millet’s painting was rejected by the French upper classes – his sympathising with the lowest ranks of rural society was deemed distasteful. Banksy’s reinterpretation of the painting builds on Millet’s aim of putting ordinary people in the limelight. Escaping the limits of the canvas, Banksy reinvents these static figures, opening the painting up to further interpretation.

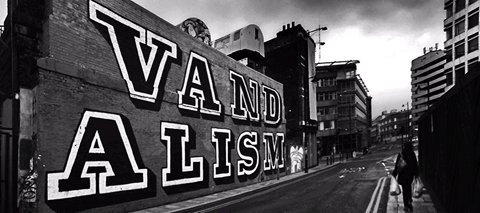

Ben Eine

Banksy is notorious for transforming perceptions of street art. His close friend and contemporary, Ben Eine, has also caused a stir with a spray can. Challenging opinions on street art, Eine started his career by spraying words like “Vandalism” across walls. A few years down the line, David Cameron is paying him £2500 to create a birthday card for Mr Obama. Ben Eine has also caused a stir with a spray can

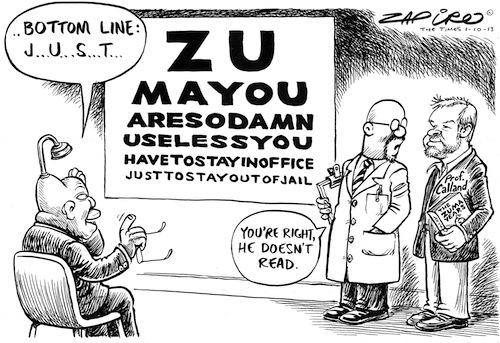

Zapiro

Continuing along the vein of presidents and their interaction with art, we reach South Africa. The country’s most famous cartoonist, Zapiro, has a string of controversial cartoons – and consequently lawsuits – to his name. Sketching President Jacob Zuma’s rape allegation was one step too far for the powers that be: in 2012, an outraged Zuma attempted to sue. Rather than meekly complying with Zuma’s demands, this incident merely added fuel to Zapiro’s fire. A recent sketch portrays the President as illiterate, unable to read “ZUMAYOUSODAMNUSELESSYOUHAVETOSTAYINOFFICEJUSTTOSTAYOUTOFJAIL.”

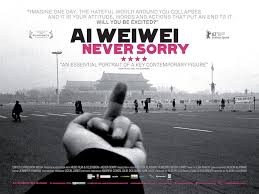

Ai Weiwei

The same attitude towards authoritative powers is shown by Chinese artist, Ai Weiwei. Indifferent to fame and financial profits, Ai Weiwei uses his art to criticise the Chinese government’s stance on democracy and human rights. The government’s reaction? To close down his blog, beat him up, bulldoze his newly-built studio and hold him in secret detention. Playing these brutal instances to his advantage, Ai Weiwei’s documentary film “Never Sorry” seeks to raise awareness on China’s strict censorship and unresponsive legal system.

Ai Weiwei criticises the Chinese government’s stance on human rights

Anonymous

In the digital era, hacker groups like Anonymous combine a strong brand image with the premise of operating on ideas, rather than directives. You might recognise them by their distinctive V for Vendetta-inspired Guy Fawkes masks. As Quinn Norton from Wired magazine says, “You’re never quite sure if Anonymous is the hero or anti-hero. The trickster is attracted to change and the need for change, and that’s where Anonymous goes.” The trickster is attracted to the need for change

These moments in history reveal the multifaceted nature of design. Like May Day revolts, they represent something intangible. Spanning almost two hundred years, these creations are united as they clamour for change. Entrenched in political concerns, social taboos or testing the boundaries of what we consider to be “art”, their unexpected approach continues to unite and divide opinion.